“And they went to sea in a sieve.”

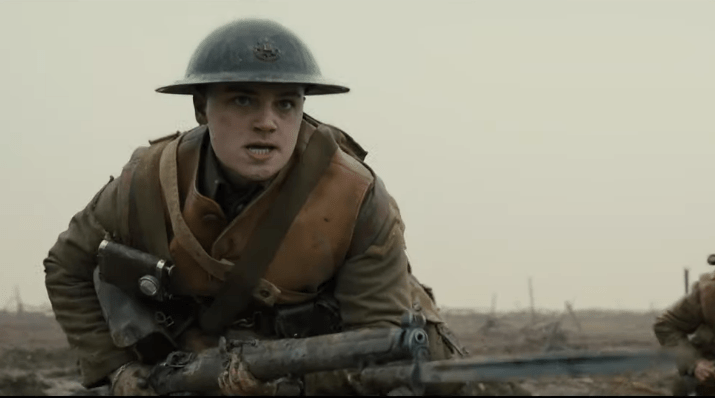

Notice: The following contains spoilers and rambling thoughts about the movie 1917.

If you want focused writing, read The Atlantic.

1917 is a story of great scope and large movement told in a personal way. The film follows two British Lance Corporals throughout their mission to belay an attack scheduled for the next day; The Germans have laid a trap which will slaughter 1,600 men if the attack proceeds, including the brother of Lance Corporal Tom Blake.

Lance Corporals William Schofield and Tom Blake seem at first glance to be an odd couple. Schofield is clearly the less enthusiastic of the two, pleading with Blake to stop and think the journey through. Prior to the movie, he trades his medal earned from the Somme for a bottle of wine and cynically brushes off the medal “men have died for” because “[he] was thirsty.” Blake, on the other hand, takes the ideals behind war more seriously. He defends the medal, and in doing so defends the dignity of the men who died at the Somme; Their commemoration, to him, should be worth more than a bottle, although Schofield counters his naivety by sharply reminding him that “[he wasn’t] there.” From the moment he leaves the dug-out briefing, Blake walks urgently to the stepping-off point. He is also more optimistic – despite being in circumstances where he is literally “stepping on the dead,” he continues telling jokes throughout the journey and recounting stories of his family’s cherry orchard, noting that after the war, “you’ll have more trees than before.”

This journey is enhanced through camera work. Director Sam Mendes and his cinematographer Roger Deakins have set the movie up as one long take, not cutting away or using insert shots. Although hidden cuts were used, with the exception of the trench collapse and the sniper shot, the movie does feel continuous. In the beginning, admittedly, this was a distraction, and some of my attention was drawn from the movie to wondering how the camera executed certain tricks. But aside from these first ten minutes or so, the “one-take” format doesn’t feel like a gimmick. These two men are on an epic journey, treading on ground that has been unoccupied by the French and English for three years, and the length is magnified through the long takes.

Tension pervades the movie. From the moment the lance corporals step out onto No Man’s Land, the thought of a bullet or trap cutting them down is never too far from the viewer’s mind. Death comes unexpectedly, in the form of gunfire and hazards both man-made and natural. The sound editor, Oliver Tarney, crafts the sound to illustrate the danger of even the squelching mud in No Man’s Land, and the gunshots against near-silence startle the audience as well as the characters. Early in the film, the two discover an abandoned German trench emptied of everything but hanging sacks of meat. Their confusion over this lasts too long – the Germans counted on the numerous rats eating the meat and triggering explosives to cave in the whole trench and kill pursuers. This speaks to the Ahabic nature of the Germans throughout the film; They seem to take every chance to harm the English throughout losing situations instead of ever surrendering peacefully.

The film’s levity is cut fairly quickly. Despite Blake being the one personally invested in the mission, and the focal character through the first twenty or so minutes, he is stabbed to death by a German pilot near a farmhouse. Mendes presents the sequence masterfully; Blake and Schofield notice two planes at the outset of their mission, but they’re friendly. They then see a dogfight between these two and a German, entirely from the perspective of the ground – Deakins has the tense, high-speed aerial hunt look slow and lazy from their vantage point. The German plane is shot down, falling out of sight behind a hill but suddenly, terrifyingly, rising up in its last moments to engulf the barn around our soldiers in flames. Blake’s devotion to morality comes to the fore in this scene as he helps the pilot out of the wreck and sends Schofield for water. A fatal mistake: The pilot stabs him, and pointlessly so, as he is shot in the next second by Schofield. The entire situation’s futility is stabbed deeper into Schofield when a truckload of British soldiers arrive at the farm, knocking Schofield loose from a stupor at losing his friend.

Though Blake dies at this point, the situation serves as a comparison between his character and Schofield’s. Blake believes in the mission, but Schofield, despite his cynicism, continues resolutely when it would be easy to leave his task. When he removes Blake’s dog tag, he also takes the letter and puts it in the tin he keeps next to his heart, a clear signal that he’s adopted his friend’s ideals. And even before Blake uses his dying wish to urge his friend onward, Schofield braves his hand being gashed by razor wire and being blinded in a trench collapse, refusing the chance to go back. He has traded in his medal, but not his morals. Mendes executes Blake’s death poignantly for this comparison, but in my opinion, slightly early – holding off and letting Blake’s character develop a little further would have allowed for a deeper response at his demise, as well as more interplay between the two instead of Schofield going it alone for the majority of the film.

The film makes effective use of high-profile actors, despite their minor roles. Andrew Scott is the lieutenant in command of the point where they must cross over, and his cynicism eclipses even Schofield’s. Memorably, Lieutenant Leslie asks the pair to throw back the flares he gives them as the Germans inevitably shoot them in No Man’s Land. Mark Strong plays Captain Smith, commander of the convoy that takes Schofield from the farmhouse to Ecoust, and Benedict Cumberbatch plays Colonel Mackenzie, in charge of the attack Schofield has pledged to stop. Their stories are rich but perpendicular to Schofield’s – Mendes hints at Leslie’s undefeated yet exhausted spirit through heavy use of a flask as he berates his men, whom he knows by name. Smith speaks to Schofield as one veteran to another, advising him that “it doesn’t do to dwell on [death,]” as the lance corporal knows. Mackenzie’s story is likely the most traumatic, but seen the least; His facial scarring implies a personal cost to his section of the war, as does the tirade he gives against delaying. He wants vengeance, and to have done with the fight, but the audience is given no further information on him.

The long take emphasizes the weariness that follows such a journey, as does the symbolism of the character’s dress. Both soldiers start off fully kitted out, with gear that is (for the trenches) clean, and extra equipment such as flares and grenades for the German trenches. Along the way, however, Schofield loses his helmet, his pack, and his rifle, and ends up with nothing but his uniform and the letter from the general containing orders to stand down. The truck leaves him at a canal by the French town of Ecoust. The bridges are blown – more German handiwork – and Schofield encounters sniper fire making his way across. His battle with the sniper consists mainly of hurried running, fear of the next bullet, and Tarney’s excellent sound design, but few actual shots. The sniper and him shoot each other simultaneously, and this gives the audience the second clear cut of the film while Schofield lies unconscious until dusk.

Waking, he moves through the town, and finds it occupied; His first meeting with a German is more awkward than anything, at first. The two see each other and hesitantly approach, until they finally recognize their respective enemies and Schofield breaks running. With the entire town in German hands, and much of it on fire, he finds solace in a cellar with a French woman, Lauri, and her baby, a war orphan. Just as Deakins expertly accommodates the camera in tracking shots of Schofield, Mendes smoothly transitions between the large-scale Hellish nightmare above and this personal tragedy below. Both places are surrounded by darkness with small points of light, but the fire in the town swallows buildings whole and threatens Schofield, while the small lamp in the cellar brings calm to the three, freed from the war through distraction for a few minutes but never free of its consequences.

Schofield gives all his supplies to Lauri as the sun begins to come up, running through Ecoust without his helmet, desperately choking a soldier to death after trying to take him peacefully and losing his rifle in the process. He braves this and dozens of gunshots in the dark to escape the town and follow her directions – following the river downstream will take him to the Devons, the regiment he must warn, and as bullets close in, his only recourse is to plunge into the dark water. The current takes him away, throwing him through riptides and over a drop, but he eventually floats calmly as the river stills, surrounded by cherry blossoms. The war quickly ends the interlude and makes its presence known, though. Schofield reaches a dam of logs, and he isn’t alone – grotesque corpses surround him, and he must once again step on the dead to prevent more from being made.

Stumbling and soaked, he makes his way to a group sitting around a singer and slumps against a tree, catatonic. The melody is haunting and entrancing; His experiences and the overwhelming nature of the moment lead to Schofield overlooking that the men around him are obviously prepared for battle, but after a moment he realizes that the Devonshire Regiment surrounds him but morning has arrived: The attack has started. Schofield, at the end of his journey but minutes too late, sets off on a mad dash, a final race against time to find Colonel Mackenzie and call off the remaining waves. His failed efforts to do so with other officers reflect 1914, when byzantine political machinery created over years made one man’s death the cause of a world war. Too much preparation has gone into the attack for anything less than the colonel to stop it personally, even with orders from High Command, and this urgency leads Schofield to sprint and shove his way through the invasion force, going over the top before an attack is even called to move further down the line. This shot is in the trailer, and rightfully so; Tarney conducts the cacophony of warfare like a symphony, and Deakins frames the shot perfectly to emphasize the stakes Schofield is personally under. Each man that runs past him before he can reach Mackenzie is another casualty, just like his friend, and every passing second not only cheapens Blake’s sacrifice, but also makes Schofield’s promise to protect Blake’s brother look more hopeless. The white chalk from the trenches covers him, reminding the audience of the many, many dead that would be produced by the attack and also the purity of his intent. He has dropped all his cynicism, and risks his own life for his friend’s ideals.

After more than a day of fighting and running, Schofield’s last delay is the most ironic, yet the most fitting – the guards outside Col. Mackenzie’s dug-out won’t let him in. And even when he forces past them, Colonel Mackenzie is violently opposed to the order, listing every circumstance where High Command has failed his men over the years, and the audience believes for a lingering moment that the entire mission might be a failure. Ultimately, Mackenzie only stops upon learning of the trap. Appealing to higher orders on the frontline does nothing, but the desire to protect his men and the belief that the Germans would spring a trap resonate with him, and the men are stood down.

The few minutes of combat is enough to bring forward the film’s last moment of suspense and hopelessness. Casualties stream by as Schofield asks for Lieutenant Jack Blake, and he’s told offhandedly that the lieutenant went up in the first wave, with his men. Schofield shouts at every triage tent, before finally getting a response. Richard Madden gives a sharp, effective performance, cheerfully asking where his brother is before his face tells the story of his realization. We see Blake in his older brother; Despite the devastating news, the lieutenant holds it together, crying but still speaking with Schofield and bringing his wounded men in. “Will,” as he introduces himself, adds a bit of his personal experience to the war when asking if he can write to Blake’s mother: His dead friend wanted him to write that he wasn’t scared, and that he loved his family, but Schofield also adds that he wasn’t alone. The heartfelt, awkward exchange leads to the last scene of the movie.

Schofield lies against a tree amidst a field of dandelions and scattered poppies, just as he did in the beginning, reaches inside his shirt, and opens the case in which he keeps the photos of his family. This symbolizes human connection – throughout the war, Schofield has had to hide his in order to protect himself, only allowing himself vulnerability in brief moments as with the baby, or in terse exchanges between soldiers. The film, which could have easily ended in a total loss to make a greater point about war, instead chooses to remind us about the cherry tree, and hope for the future. For fans of cinematography, subtle storytelling, and realism in action, 1917 is a must-see film.

A